ASFB: Like Ferris wheels in a windstorm

Editorial

On my way to the State Theatre with my life partner Billy, I confided that the last time I saw a professional dance performance was more than 15 years ago. He asked, rightly, what I thought of “The Nutcracker.” “I liked the sets,” I said adding, “I bet there aren’t any sets tonight.” Candidly speaking, I was dreading that modern ballet, like the most tedious fruits of modern theater (think Sartre’s “No Exit”) was bound to be a serious, uncomfortable and lengthy affair—like a Siberian train ride or a Target corporate job interview.

What a joy to find the Aspen Santa Fe Ballet program divided into three concisely executed and digestible pieces with luscious fifteen-minute intermissions between each. In my experience, generous intermissions are what keep high art, no matter how great the performance, from feeling like homework. (That’s a topic for another day.)

Mind you, I know nothing about dance from a critical standpoint. As an architect, I feel qualified enough to write about architecture and urban design and other static human efforts. Writing about ephemeral experiences like dance, however, is completely out of my comfort zone. At least with buildings you can return to photos or the place itself to test your memory. With dance you, and I, can only rely on personal impressions and memories of a singular event. Very frightening, and yet people do it all the time. I was encouraged. But a little research would help.

In an attempt to educate myself, I scoured the program for director notes or some form of dramaturgy to give me a foothold on interpreting the performance. No dice. The title of the first dance, “Uneven,” was all I had to run with. I noted there were eight dancers. Aha! Two times two times two equals eight–-a doubly “even” number if ever there was one. “Uneven” must be an ironical diversion, I thought.

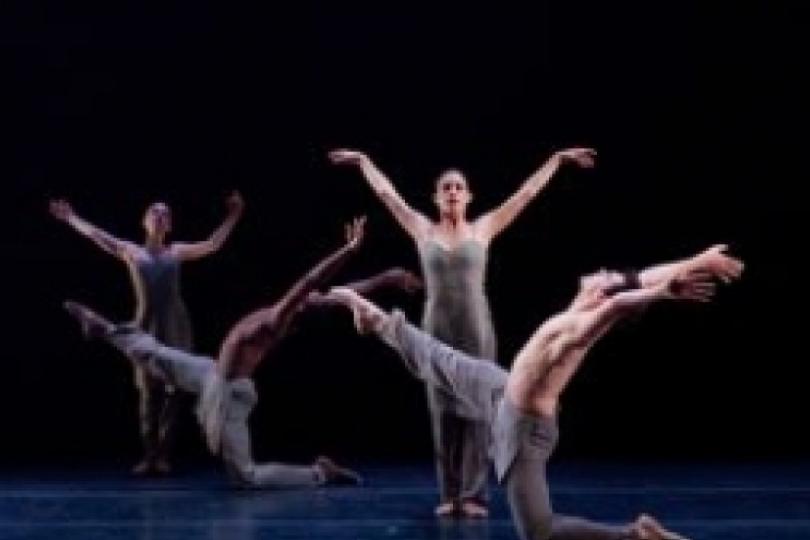

The curtain opened to a black and empty stage, except for a cellist who sat off to the side in a ray of light, playing a duet with a pre-recorded electronic soundscape. Dancers entered in conventionally matched boy/girl pairs. The men stood behind the women, who swept the air with their legs and arms in loose conformance to the repetitive music. The women folded their bodies, bounced off the floor like weightless party balloons, and rotated like floppy ragdolls. Gravity seemingly had no hold on their animated origami. Meanwhile, the guys--their powerful legs spread in A-frames to create a sturdy base for all the lifting--gripped, flipped and balanced their partners with impossible ease. It was like watching side-by-side Ferris wheels in a windstorm.

Eventually the pairs dissolved into other pairs and synchronized groups. Angular movements were interrupted by spontaneous hand tremors. It was all irrational, complex and beautiful—and by beautiful, I mean the dancers’ bodies were beautiful. The men wore white long-sleeve shirts that fit like skin, and tight black boxer briefs with legs fully exposed. Similarly, the women wore garb that resembled one-piece swimming suits. For the first 10 minutes, I just sat back and appreciated their zero-percent body fat.

Thought went away. Groups and pairs dispersed and recombined. The music ebbed and rushed, the cellist’s bow jabbing in bursts as two men drew imaginary bowstrings toward their target (a he or a she?). Cut to black. Curtain.

What?

Feeling like I missed something, I headed to the lobby for a little architectural Rococo excess and to gather my wits (and a bottled water for Billy.)

Within minutes, it was clear the second piece, “In Hidden Seconds,” was the numbers game I’d anticipated with “Uneven.” On the stage, black again, a sole woman stood over a lump on the floor. Unlike “Uneven,” which was leggy and angular, the motion and effort in this piece was all upper body. A second female dancer entered from stage right, mimicking? taunting? paying homage to the first? They become a matched pair. The lump on the floor awakens. It’s a guy. Two to one now.

Three dancers play off each other wearing gauzy grey pajamas. Two more men step in: five on stage total. Groupings emerge, subdivide. Movements are synchronized, then spinning and twisting. Five women to one side, four men on the other. Recombining. Three men in front, two women in back. And so on. The stage compositions are most striking when the dancers pause for a moment, poised for the next move. They’re arranged in insanely well-proportioned groupings, Easter Island statues dotting the stage, or in perfectly balanced tableaus on par with any canvas painted by George Seurat.

Entrances and exits are at first mysterious, as bodies emerge from the fog up stage. Then the rear wall is literally broken as dancers part a curtain of vertical black strips, stretching the strips into momentary diagonal ruptures, then racing through them like gazelles dashing in and out of the brush. The music ends, just as the pajama party disappears through the vertical strips.

Back to the lobby, this time for liquid reinforcement (cheap white wine) and another look at the program. Why aren’t there any director notes?

Finally, in “Red Sweet,” we arrive in the land of “assumed meanings” that are the stock and trade of my more regular beat—architectural criticism. Architecture cannot work without its game-box of familiar and classical references, even with the most minimal and pretentious “original works”—i.e., nothing has been done before, really; we’re only reinterpreting and expanding on the past. Same with contemporary ballet, apparently, because I recognize a Michael Jackson moonwalk when I see it.

While set to a classical backdrop of Vivaldi and Biber concertos, “Red Sweet” is rife with contemporary and pop culture references. To begin with, the ensemble is dressed in black patent-leather looking tank tops: fitting for a troupe of back-up dancers for a Britney Spears concert. Along with the saturated red and purple lighting, I can only imagine these choices are tongue-in-cheek commentary on (or embrace of) the convergence of contemporary popular culture with the earnestness of “serious” ballet, however modern that form may take.

The overall arc of the piece is segmented into small and large group performances aligned with the score. While the dancers’ movements are a choreographic visualization of the music’s intertwining melodic and harmonic currents—stimulating enough—the movements are further punctuated by a kind of broad choreographic comedy. In addition to the moonwalking, there’s a robot dance, a crab walk, variations of running in place, some overtly “fake” en pointe ballet moves, and an ersatz figure-skating pair.

I declared to Billy that “Red Sweet” was post-modern, a self-conscious collage of iconic dance references from both classical and popular culture; a mash-up of received meanings. He thought it was… nice; the most conventional fare of the evening.

I’m inclined to think we’re both right. In Billy’s favor, the dancers obediently moved to the music. The pieces had clear beginnings, middles and ends. To my favor, crab walking is not one of the five traditional ballet positions (which, yes, I looked up).

I’m also inclined to think we were really lucky to see some amazing modern ballet/dance/attractive people moving on stage. Whatever you call it, we’ll be back for more.