Best of 2013-2014: Cabaret and Ashland

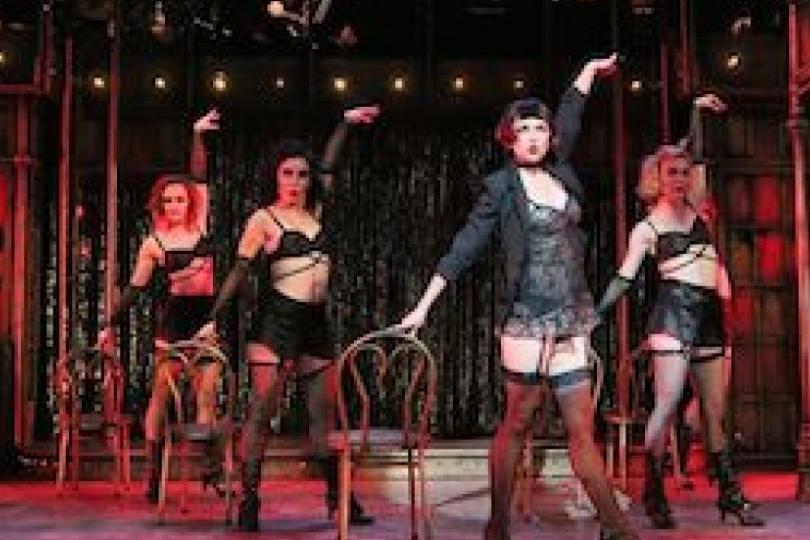

Editor's Note: For the last four years, we've honored the new theater season with a look back at what made for great work in the past theater season. If you enjoy what you read here, please help us pay for more great writing by joining our Indiegogo campaign. And enjoy the Ivey's tonight! Come back later in the week to read Dominic's recap. It’s unfortunate the phrase “adult pleasure” has connotations that can’t be wished away. Because that’s what I’m celebrating with my two choices. Adults are pretty complex creatures—likewise, our pleasures, to truly satisfy, need to hit us on several levels at once. But there’s an insidious separation in our culture between something we enjoy and something of really high quality. Immediately the question arises—isn’t “quality” a matter of taste? In my review of Three Musketeers and Dirt Sticks I tried with little success to define an objective criteria for quality in storytelling. But I’m a very stubborn person—and I take these questions seriously (sometimes too seriously). When I used to write fiction, it puzzled me authors like Dan Brown and John Grisham were so widely read—not because I don’t like plot—I love plot—but the books were not only clumsily written, they were over-blown and actually pretty lazy in the plotting. Then I took a long flight—I think it was NYC to San Francisco—and turned to see the person next to me open up a massive bestseller and sink into it like it was a big, fluffy chair. I got it. Those books—like eighty percent of television and an alarming percentage of theater—are benign narcotics, meant to help us pass the time in a pleasant and harmless way. I’m not against pure entertainment—far from it. But I’d argue even pure entertainment for adults—needs to have more than one level to it—needs not always to challenge—who wants to be endlessly challenged, really—but to stimulate. Like our bodies—which can get sludgy if we don’t exercise them now and then—our brains enjoy being taken out for a pleasant stroll among the flora and fauna of witty and beautiful language, intelligent construction, and genuine emotional engagement. Which brings me to my “Best of” last season. Cabaret, a co-production of Theatre Latte Da and Hennepin Theatre Trust in January of February of 2014 at the Pantages Theatre, was an exhilarating piece of Broadway professionalism. The mid-60s to late-70s, when Cabaret was created, saw a fascinating renaissance both in film and music-theatre. Young directors and writers added new and deeper levels to familiar tropes and genres without dismissing what made them work so well in the first place. Cabaret was born of this impassioned revisionism. Peter Rothstein’s production was glitzy, glamorous and gloriously well-acted, directed and designed. There’s a kind of delirious pleasure from sitting through a good story so expertly told. Sometimes I feel the avant-garde and the commercial world conspire in their rejection of this giddiness—the Puritanical roots of our culture demanding we either experience “something of value” or participate in a purely financial transaction—goods-for-services. Real theatrical joy is rarely on the menu. Transatlantic Love Affair would probably see little in common between their beautiful and elegiac Ashland and Cabaret—but they are cut from the same cloth. Ashland creates a desperate family farm and the equally desperate community around it using only the actors—no sets, very little lighting. Just arms and legs and bodies—gorgeously sculpted and choreographed. Those skeptical about the meshing of dance and theater (so often dance overwhelms) need only watch the movements crafted by Diogo Lopes and the company for this piece—beyond natural human movement, yes, but still short of all-out dancing. True Dance/Theater. Just as in Cabaret, the mix of rigorous professionalism and theatrical joy reminds you what theater is all about, what the ritual of theater is for. In my initial review of Cabaret I laid out my desire to break down the wall of parochialism separating fans of that show from those of Ashland. It’s an aesthetic war that’s been going on for a long time: text versus movement, naturalism versus theatricality, linear storytelling versus poetic evocation, plays versus musicals. The War’s over. Everybody won. Not only are small theaters across the country present-ing every conceivable flavor of theater—larger Regionals are getting into the act, allocating considerable resources to artists like Mary Zimmerman, The Moving Company, Culture Clash and The Civilians. Did it take the bigger theaters decades to catch on—sure. That’s called “reality”. Conceding the point admits this explosion of form has been going on for a long time. The Wooster Group devised and deconstructed their first piece in the mid-70’s. I attended a “choose your own adventure” play—where you pick which actor and story to follow after each scene—in 1987. The first “theater piece” I ever saw in someone’s apartment was in 1991 (The East Village—it was a hair cut.) Sarah Kane blasted the theater itself to pieces in 1995. If your claim to significance is it’s never been done—sorry, it’s been done. At this point, the questions are the same for everyone—how are you doing it? And why? And with what level of artistic integrity, professional rigor and theatrical joy? It’s a credit to both Cabaret and Ashland that I asked none of these questions while watching them. Because the answers were right there in front of me.