Big ideas don’t come easily. They take work to create, work to understand, and even more work to defend. Big ideas are not how modern hipsters spend their Saturday nights.

So when David Ives, whose more well-known plays (

Sure Thing, Venus in Fur) have unique twists that make them feel cool, takes a two-and-a-half hour foray into 17th-century philosophy, it feels like we’re hearing from a different playwright: one who rejects sexiness or frothy entertainment. As its unwieldy title might suggest,

New Jerusalem: The Interrogation of Baruch De Spinoza at Talmud Torah Congregation: Amsterdam, July 27, 1656 is at least as concerned with its intellectual rigor as it is with its dramatic arc. It’s a clever, witty play, and the Minnesota Jewish Theatre makes its degree of rigor feel worthwhile, but like all big ideas, it isn’t easy and it definitely isn’t hip.

Unlike the kind of philosophizing you might have done in college over a joint or a box of wine, there were real political stakes to new ideas in 1656. The Jewish community, fleeing repression in other parts of Europe, had found a safe haven in Amsterdam, but government tolerance came at the price of some strict regulations on freedom of expression. In developing (and openly discussing) a new perspective on God and free will, Baruch de Spinoza deviates from Jewish doctrine to such an extent that it threatens the security of the entire population of Jewish refugees. When the congregation places him on trial, he potentially faces

cherem, the harshest form of excommunication from the Jewish community.

In essence, Spinoza’s trial pits his cherished ideas against all of the people and places he holds dear. These extreme stakes are what give the play its backbone, but the substance of the evening is the philosophy itself. This is particularly true because Spinoza is

not imagined as a particularly likeable character. He is childlike and pretentious, though obviously brilliant. Since you wouldn’t want to hang out with him, you have no choice but to focus on his ideas. And thanks in large part to Michael Torsch’s engaging and focused acting, his magnetism makes you root for his intellect, if not his personality.

Characters in counterpoint

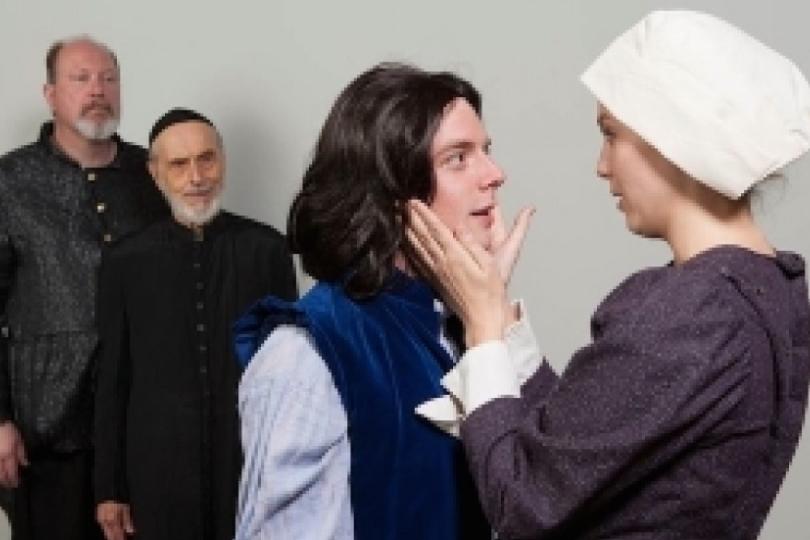

Many of Spinoza’s interlocutors provide a good counterpoint to his impulsive, playful attitude. George Muellner gives a particularly well-balanced performance as Spinoza’s former teacher, Rabbi Saul Levi Mortera, who is torn between his love for his student and his loyalty to the Jewish community and religious tradition. Skyler Nowinski plays another of Spinoza’s judges, Gaspar Rodrigues Ben Israel, with deadpan hilarity, particularly if you’ve grown up around Jewish stereotypes. (Despite the fact that this production is by the Minnesota Jewish Theatre, Ben Israel is the only character that non-Jews might have a harder time relating to – or feeling comfortable laughing at.)

There are a few supporting characters that feel a bit miscalibrated: Spinoza’s sister Rebekah (Rachel Weber) is unrelentingly shrill and goes through a strange transformation at the end, while James Ramlet’s portrayal of local leader Abraham Van Valkenburgh is full of booming authoritative gravitas, but never evolves from there. On the other hand, Briana Patnode plays Clara Van Den Enden, Spinoza’s love interest, with a gentle conviction that provides a lovely change of tone from the testosterone-fueled intellectual sparring going on around her.

I have to admit that I knew very little about Spinoza going into the play, so I made a desperate detour to

Wikipedia from my seat at the Hillcrest Center Theater before the play began. (And here, I need to digress, because the uncomfortable seats at the Hillcrest were one of the play’s few challenges that were not pleasant. Hip replacements or back problems, be warned.) Wikipedia, unfortunately, does not condense complicated philosophical oeuvres into bullet points: even in app form, you’ve got to put in your time to get your head around this stuff. But it turns out that I didn’t need a primer, anyway. What this play does best is provide a crash course in Spinoza’s philosophy, including all the contextual information you need to understand the political stakes of his arguments and his trial.

Why should you care?

“But why should I care about Spinoza?” you might ask. This is an entirely legitimate question, since his idea that God and nature are one and the same, though very nice, does not currently feel as urgently controversial as it did in 1656. Ives doesn’t jump through hoops to try and make this philosophy feel modern or relevant, although there are echoes of current rhetoric in the character of Van Valkenburgh, who claims that Amsterdam is “the most beautiful city in the world, and the most tolerant”, insists that Spinoza is “infecting our republic with his ideas”, and has an irrational fear that these ideas are a sign of the end of days.

No, there is very little about Spinoza that has anything to do with 21st-century America. But the process of spending over two hours engaged in heady philosophical discourse is absolutely relevant – and, to my mind, critically important – because it is something we rarely ever do. Even my search for a 5-minute dose of Spinoza on Wikipedia speaks to our persistent impulse to favor quick answers over probing questions, simply because our culture and technology have made it easier to find information than to seek wisdom. Big ideas do take work, but hard work has its own reward: there is a satisfaction and intellectual pleasure in

New Jerusalem that makes you want to keep thinking, arguing, and asking more questions.

Now take out your phone, and see if you can you get that from the Wiki.