Clowning from the Mediterranean to Mpls

Mohammed Yabdri started clowning as a 13-year-old in Oran, Algeria, but he did not really know what to use for makeup. Smearing on his mother’s lipstick and some toothpaste that cracked in no time, he took naturally to the innocence and honesty of clowning as a pre-teen.

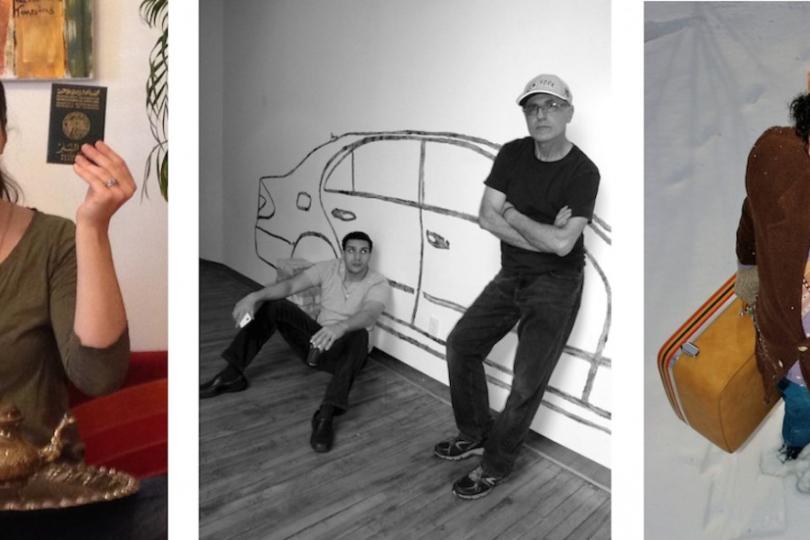

After turning to other performance styles and leaving Algeria to move to the United States, Yabdri is stepping into clown shoes again—this time sans toothpaste, and sans circus shoes. His one-man show A Clown in Exile is one of three works performing in the New American Theatre Works summer festival through July 12 at Mixed Blood Theatre. The Noah Bremer-directed show follows a nameless clown from the streets of Paris to the U.S. (“where everything is big”) on a search for a place to call home. Through the story of his travels, he’s meditating on the immigrant experience of the grass always being greener in other homelands.

New Arab American Theatre Works is a recently assembled collective of local Arab American artists. Its summer festival, a complement to Mixed Blood's 55454 Series, is geared toward expanding opportunities for Arab American artists. Joining Clown is Kathryn Haddad’s Road to the City of Apples, a travel tale about friendship and cultural norms on merging highways. There is also In Algeria They Know My Name, a reversal of the clown’s story in which a Minnesotan moves to Algeria and falls in love—written by Taous Claire Khazem, a co-founder of the collective and Yabdri’s wife.

The Language of Clowns

When he moved to the U.S. in 2012, Yabdri had only known life as a comedian and comic actor in his home country. He had never stepped on a stage here and struggled with English. Looking for a way to talk about these experiences, he met with Bremer and together they created their clown.

He is simply called Pas, the French word for “not.” He speaks four languages: Arabic, English, French and the Berber dialect Tamazight. (During our interview, we spoke English but ended up speaking French, switching between the two when it was easier to describe something in the other language.) When the clown sneezes, he says a few words in Arabic, and those around him do a double-take. Because Islamophobia is there no matter where he is in the world.

“The choice of the clown as a style and as a character is also [one] for me as an artist,” Yabdri said. “In the middle of this chaos in the world where people are losing their humanity, one just wants to become clowns and to rebuild our humanity and be honest and correct with ourselves.”

Because of their foolish innocence, clowns have a special vantage point to play with and question parts of their culture. French Renaissance writer François Rabelais wrote court jesters are "self-indulgent, witty, clever … the fool as critic of the world,” and he was right. Taking a sharp look at our humanity is a long tradition in clowning around the world. Tenali Rama, a popular jester in 1500s India, won his king’s laughs by riding on a guru’s shoulders, getting in trouble, and offering the guru a ride on his own shoulders to make amends—only for the guru to get beaten by the guards for the shoulder-riding. English court fools, as we know from our Shakespeare, could run their mouths about the royal family without getting in trouble.

Yabdri’s show uses clowning to play with the ways immigrants interact with different new cultures along their journeys. He has performed it in Minneapolis for Francophone and Fringe audiences. In 2013, he and Bremer traveled to Algeria to present it on different stages across the country.

Clowning is popular in Algeria, but it is often associated with kids’ shows and educational programs. And just like in the U.S., clowns are almost always associated with red noses, big pants and wigs. It was not until he brought the show to Algeria that Yabdri started to change people’s thoughts on that—through clowning itself.

Though his audiences had expected the standup comedy style he had been known for before the move, this new show reintroduced them to an art form they normally only saw in a child-centric or educational setting. It led to some good discussions about this performance style and its place in theater there, Yabdri said.

For a previous show, Yabdri had interviewed immigrants who illegally crossed the Mediterranean Sea to move to Spain—commonly known as “the boat people.” In these conversations, he learned that many leave because they think life is better in other countries.

“The common thing was this feeling of inferiority,” Yabdri said. “At the same time, our culture has her own riches, so why do people feel this inferiority?”

Meant for an audience of everyone, the festival at Mixed Blood will be a way for artists to reverse assumptions and stereotypes about the Arab American experience.

Composed and Decomposed

With his show, Yabdri is also tackling some stereotypes about clowning, including the notion of the clown’s costume. Having long ago discarded his mom’s lipstick and toothpaste mask, A Clown in Exile’s character wears a mixture of styles of street clothes: Nike tennis shoes, a Middle Eastern-style cap, and a mismatched blazer and slacks that could be from anywhere.

“This is the identity of people in the world now. We need to say, ‘oh, people are a mixture of culture, of energies, what we read, what we listen; what we see, what we eat,’” Yabdri said. “So this character is little bit of everything.”

After so much traveling and searching, the clown wears only a swimsuit at the end of the show before taking a dive—into what?

“Décomposition?” Yabdri asked in French, only to confirm that in both languages, the words were the same.

But, ultimately, you’ll have to see it to fully understand.