Catharsis: From Aristotle to Freud to an Egg Salad Sandwich

Editorial

Is it time to have another argument about catharsis? More rhapsodizing about the sublime effect of emotion sweeping over the audience? More counter-arguments from structuralists who think that emotion is pointless fluff distracting us from the real thing?

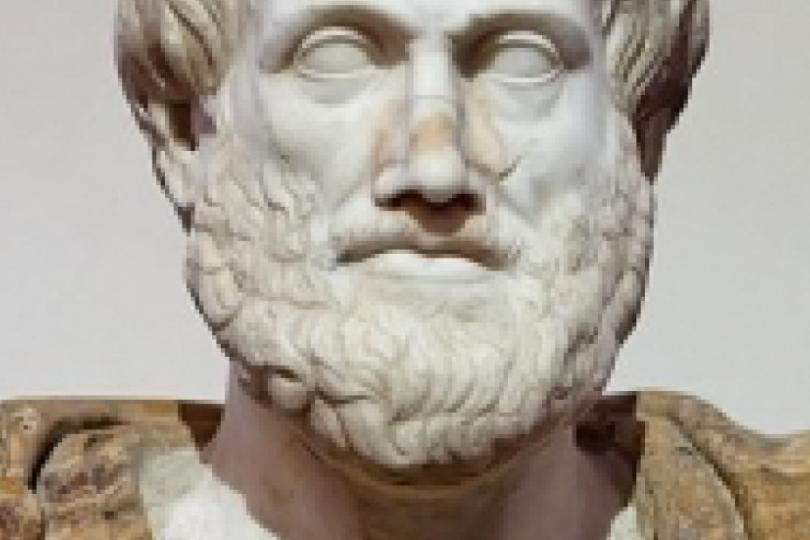

We can blame this whole mess on Aristotle. To be more precise, we can blame generations of Western philosophers and writers who thought that every word out of the man's mouth was infallible. Aristotle said a lot of things. Some of them were correct ("the sun is bigger than the earth"), some were flat-out wrong ("four, no, FIVE elements!"), and some were kind of correct, but needed someone who was actually interested in doing empirical study in order to make them complete ("everything is made of Atoms!").

If you want to have an argument about catharsis, you need to go back to Aristotle and read the Poetics.

If you read closely, you'll find that he never actually gets around to defining the word. We think the word has its roots in the Greek words for "purgation" and "cleansing" (again, "we think" because he never defined it, no one that we know of used the word before him, and no one really used the word again for several centuries after); but how literal was he being? Was he speaking in metaphor, or was this meant to be a technical definition of verbal vomiting? We honestly don't and can't know, because, unfortunately, Aristotle is rather dead.

Aristotle, like many of his Greek philosopher contemporaries, often made sweeping proclamations about the way the world worked based on his own observations without doing any kind of inquiry. This is why being a philosopher is great. You get to make things up and state them as if they are fact. Sometimes you get lucky and scientific inquiry backs up your wild assertions; or you say something farcically unsupported, nobody questions you on it, and you wind up in elected office. Most times, though, you're ignored until someone needs to have an argument that in no way advances anything, which is what happens whenever catharsis is brought up, either in a philosophical or arts discussion.

And always, always, always keep in mind that, as bright as Aristotle and his fellow Greeks were, they still believed that sickness could be caused by having too little yellow bile and that flies generated spontaneously from poop. This was a world where soap had barely been invented, so let's take their assertions with a grain of salt. Even if they were more or less right, we've figured out quite a few refinements since then. Like pants, for example. Pants have definitely come a long way since then.

Before we start waxing on poetically about the emotional cleansing power of art's scrubbing bubbles, I want everyone to go back to the beginning and look at what Aristotle plopped on us.

For starters, Aristotle was focused on the written language of a play. It's about words, words, and more words, but fails spectacularly to address those times when a simple gesture and a wordless moment can bring the audience to tears.

Second, it is applied only to Tragedy (the big, fat, Greek kind, with the capital T), and all of its very particular trappings, forgetting entirely about Comedy, let alone any theatrical conventions we've invented since then.

Third, and I believe most important, catharsis is just the beginning. In Aristotle's own writings, that emotional purging/vomiting/cleansing isn't the end or even the point. It's a step toward what he called rhaumaston, meaning wonder and awe. As Aristotle himself put it, the point wasn't how much a play made you feel, but how much wonder it revealed to you about the world.

Step back, extrapolate that for a moment. It's not feelings. It's wonder. It's awe. You can derive wonder and awe from a Mandelbrot Set, from the shape of a leaf, from understanding the underpinnings of planetary motion, and nowhere in any of those things do you need to be experiencing someone else's emotions. And awe doesn't mean that you reach some warm, fuzzy conclusion. The actual definition of awe is to be overcome, not by emotion, but by EVERYTHING. Truly experiencing awe is being lifted outside of yourself and, for a moment, glimpsing the world the way a god might and feeling your brain fried as it tries to comprehend twelve different dimensions.

Heady stuff, I know. If anything, rhaumaston is vastly more interesting than just having a sad because Oedipus stabbed his own eyes out after having sex with his mother. You can skip right around Aristotle and get to rhaumaston through comedy, drama, dance, pictures, science, meditation and plain old self-reflection. There's no need for blood, guts and wailing.

So, why do we continue to praise catharsis, but can barely remember what rhaumaston means even though we were just given a definition of it two paragraphs ago? I blame Sigmund Freud (but then, I blame Sigmund Freud for a lot of things). Freud picked up the term and embedded it in his psychotherapy practices with the tweaked definition of "experiencing and expressing intense emotions in order to overcome them." Freud took the more literal interpretation of the word whose definition isn't all that definitive and slapped it down on us with his usual innuendo-laden gusto. (Freud, like Aristotle, wasn't fond of actually experimenting with anything before he asserted it was true). And, of course, Freud being Freud, most of those emotions were wrapped up in sex. So, once again, we're just arguing because Sigmund made us uneasy about sex.

But it's easy to understand how this definition hangs around, because it's easily confused with empathy. Empathy is what makes it possible for us to watch and enjoy theater in the first place, since it allows us to project outside ourselves and use those prodigious mirror neurons in our heads to imagine ourselves in someone else's place. But, catharsis, as we understand it through Freud's bastardization, is not about gaining insight into someone else's feelings; it's about experiencing your own in order to purge them.

That's a huge distinction. Empathy is a well-understood, well-tested phenomenon that is at the very root of what it means to be fully human and has been demonstrated in literally thousands of controlled

scientific tests. Catharsis, as we know it now, is Freud's loose, made-up interpretation of Aristotle's made-up word that he never clearly defined in the first place to apply to a specific type of theater in a specific era that hasn't existed for thousands of years and is only argued about about amongst philosophers and artists.

So, let's sum up: (1) catharsis may not even be a thing; (2) if it is a thing, it's not the most important thing; and (3) it's not even necessary for getting to the most important thing.

I know that's not the sexiest, funniest or most compelling interpretation of catharsis, but as I understand it, I don't find catharsis to be sexy, funny or compelling. It's like vomiting after eating a bad egg salad sandwich. Sure, you probably feel better after you do it, but there was no reason to voluntarily eat the sandwich in the first place. See? Not sexy, funny or compelling, is it?

I guess what I'm trying to say is to find a good deli, order the sandwich that you like and quit worrying about whether or not you're enjoying the pastrami in the right way in order to achieve perfect sandwichness, because, in the end, you'll only enjoy the sandwich that you like, not the one that Aristotle says was perfect and true.

Or maybe it's just that I skipped lunch to finish writing this.