Is the Fringe still Fringey?

During the festival’s opening weekend, I wrote that it felt like the Millennials were taking over—that there was a palpable vibe, at least on the opening Thursday night, that there was a changing of the guard afoot. Now, a lot of that could be because there has been a changing of the guard over the last couple of years: Of the six people who were on the year-round staff in 2013, only two remain in 2015. For many arts organizations, this would be an upheaval on an unheard-of scale, especially considering the aggregate service of the four departing staff members totaled just over 40 years by my calculation. Turnover at Fringe is astonishingly low. And it is curious to see both how much and how little Fringe has changed because of this revision of the core staff.

The festival is being run well. It’s great. It’s pluggin’ along. Go, Fringe. This year’s box office issued 50,330 tickets, a record for the festival. But, depending on how fast and loose you apply the rounding, that number has been hovering around 50,000 for five or six years, and has been steadily approaching it for at least a decade. The festival certainly didn’t go through a growth spurt this year—but, then, the days when everyone was genuinely dumbfounded by exactly how many people were showing up have passed.

It could be that Fringe the organization has found its spot in the world. I don’t want to say “plateau,” because that—in capitalist societies, anyway—implies stagnation. As long as Fringe remains open both in content and in access, it cannot be stagnant. But maybe this is about as big as Fringe gets. Maybe it has reached whatever equilibrium it was destined to reach. Maybe this is the best possible iteration of Fringe because it is the most economically efficient at delivering non-juried, hour-long performing art pieces to the greatest number of people willing to pay for them and a button.

After all, Fringe means crowds now, if a somewhat predictably sized ones. The question on everyone’s lips has become: Where will the crowd show up?

Crowds or catharsis?

When I was talking with my pals Kate Hoff (former Fringe board president and artist herself), Bob Weidman (Kate’s husband) and Wendy Ruyle (long-time Ultra Pass holder and designer of more show postcards than just about anyone) and we discussed which of the top-ten shows (calculated both by total number of tickets issued and by percentage of house capacity) we had seen, we weren’t too surprised when we discovered that I saw zero, Wendy saw three, and Kate and Bob saw two. In most years, at least one of us would have seen all ten.

Now, Kate said she liked everything she saw: “Lungs was terrific and I was very happy with Brother Ulysses.” And we all agreed that the Bring Your Own Venues—“I think they call them ‘site specific’ now,” Wendy corrected me—was a welcome move. But Wendy followed that up with, “You know, I didn’t see anything that blew me away this year.” And we all nodded knowingly. This feeling is familiar.

“There was no Cody Rivers,” said Bob.

When I pointed out that The Cody Rivers Show: Flammable People, a mind-bendingly inventive show by two physically gifted goofball comedians from Washington State who stole everyone’s hearts, was in the festival eight years ago, we were struck with a moment of sobriety. If Cody Rivers is still widely understood as a benchmark for originality, that might be trouble.

But maybe it’s just our benchmark for originality. The reason that everyone loved Cody Rivers was because we had never seen anything like it. It was revelatory. It was stimulating. It showed its audiences something new, and it made us all crazy with love and joy. But in social psychology, there’s a thing called adaption-level phenomenon; it means that humans judge the qualities of our experiences relative to past experiences. So we think of things as hotter or colder, louder or softer, crazier or drearier based on a running average, not on a set level. So sometimes it’s a struggle to get excited about Fringe because, in some way, it is always wonderful. Maybe we’re spoiled. We probably are. Minnesotans, after all, excel at forgetting how much we excel.

What is new for you?

So maybe the perennial discussions asking “Is Fringe still Fringey?” are asking the wrong question. For Fringe to stay Fringey, you need to know when to back off, you know when to ease up a bit. Fringe is appealing because it’s so ephemeral. Take a break. Let it be fleeting.

So instead of a growth spurt, I’m falling on the side that Fringe’s existential nature is undergoing an evolutionary period. There were a lot of newcomers around and more than one old-timer stayed home. It’s time to watch as the Fringe gets reinvented by people who were in junior goddamn high when Cody Rivers was last in town. Fringe is best when you’re giddily discovering the beast for yourself, not when you’re analyzing it, not when you’re trying to figure out how it ticks. Fringe is best when you’re slavishly devoting the next decade or two of your life to performing, volunteering, supporting and guiding it. Whoever is entranced by Fringe fuels Fringe.

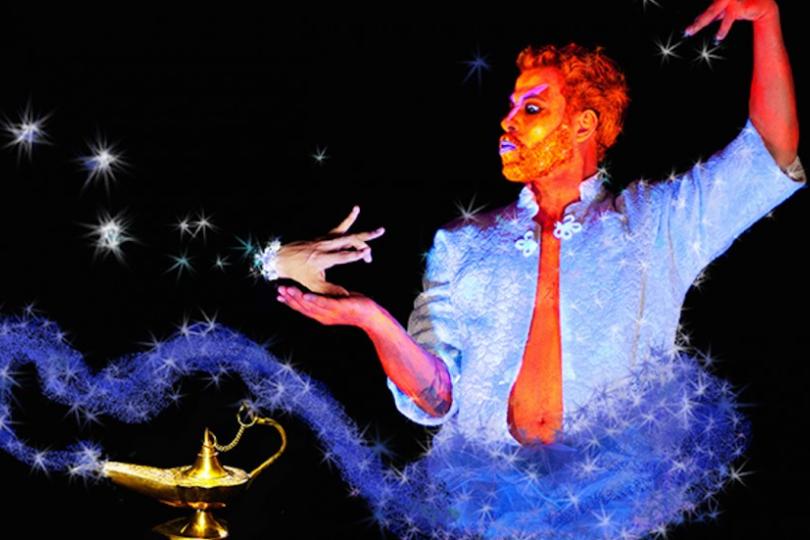

It is the festival’s most potent magic.