The future

Any conversation about the future is really a conversation about the present. Although the Playwrights’ Center’s Critical Conversation: Theater in 2060 started off with a series of personal manifestos for the future of theater, it was less a revolutionary think tank than a reflection of the most pressing issues theater artists are facing today.

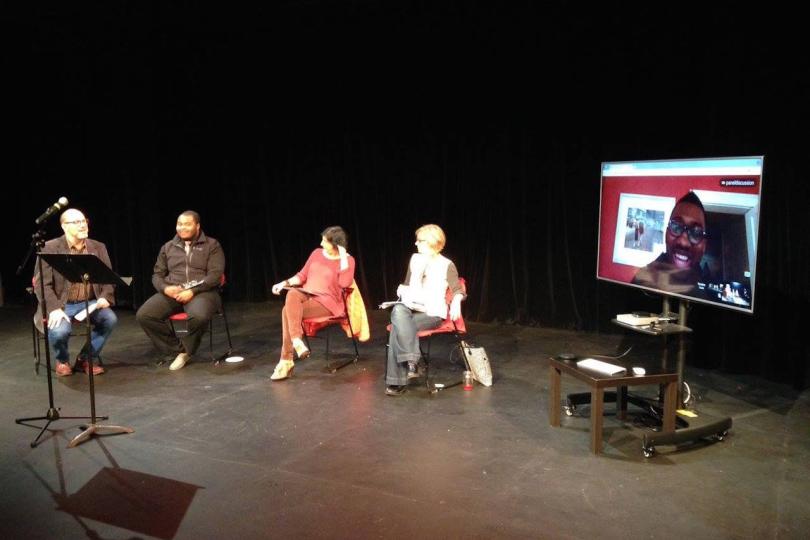

Artistic Director Jeremy Cohen, who also moderated the panel, put together a great team of playwrights and directors to weigh in: H. Adam Harris, Aditi Brennan Kapil, Kwame Kwei-Armah, and Kira Obolensky. While anyone in the theater community could probably predict some of the most common buzzwords of the afternoon (community, accessibility, diversity), each one of those words represent tensions that go deeper than feel-good aspirations for the future – and that could potentially disrupt our fundamental ideas about what theater looks like.

The issue of diversity and community-building seemed to be at the forefront of everyone’s minds, but it took a while for the panelists to get beyond the obvious, though certainly important, fact that at a time when society seems particularly fragmented, we need to be sure everyone’s voices are being heard. Kapil likened our current situation to a zombie apocalypse, with theater providing “herd immunity” to our growing sense of isolation, while Harris focused on the ways that theater can be a respite from political chaos.

Is the future in the classics?

Where it got more interesting, though, is when the group started to get into the “how” of equity and inclusion, because that was where fissures started to form between a desire for a more populist theater and a deep respect for the sanctity of the classics. By “populist,” I don’t mean “lowest common denominator” – these are smart, thoughtful theater professionals who are putting on high-quality work. But in considering how best to connect with audiences of different gender identities, ethnic origins, and abilities, there were differences between the approaches advocated by various members of the audience and the panel.

For instance, one audience member wondered whether the theater of the future would incorporate other genres such as hip-hop and spoken word, and Kapil expressed a desire for theater to break more rules and connect more with other media. In counterpoint, towards the end of the discussion, Harris told the story of seeing The Cherry Orchard at the Classical Theater of Harlem as a teenager. After seeing Wendell Pierce on stage, Harris decided that he wanted to be an actor, suddenly understanding theater as something that he was “not used to, but [that could] still be for me.”

And then there was a middle ground, with one audience member noting that Shakespeare has not been kind to women, and expressing her appreciation of the changes that Ten Thousand Things has made to Pericles in its most recent production. To these comments there was a general sense of agreement that one has to be willing to make changes to classic texts that don’t work for modern audiences.

The debate around the status of the classics is nothing new to the theater world. But in thinking ahead as far as 2060, it seemed as though the room was becoming more and more stuck in the question of the present: how do we bring the theatrical tradition to communities who have not traditionally felt included?

But the question itself presumes that these communities want the tradition we’re bringing them, or don’t have other ways that they would rather see or make theater. Maybe our traditions don’t work for everyone, and between now and 2060, we could be more intentionally upending the “rules” that could create barriers to inclusion.

Are there ways to fundamentally question the hierarchies between good seats and bad seats, the assumption that audiences will be familiar with how to “read” theater, the expectation that audiences sit silently in rows and artists look, speak, and move in a certain, familiar way? It’s not that this kind of re-imagining isn’t being done already; it’s that we need more of it, implemented more radically and spotlighted more intentionally.

Where does change come from, and go?

And this leads us to the question of where this change should come from, and here, the panelists proposed a number of innovative solutions. When asked what he would do with 5 million dollars, Kwei-Armah imagined investing in R&D to figure out how to disrupt theater in the same way that Uber and Airbnb have disrupted the taxi and real estate markets. Obolensky, in turn, envisioned artists being given “fiefdoms” to control as they will, all connected in a national network of community and neighborhood theaters.

With such potentially fruitful proposals, a lot of change could be made between now and 2060. Kwei-Armah ended the panel discussion by warning against false binaries, stating, “There are many rooms in my mother’s house… the discovery of something new doesn’t need to mean the disruption of something old.” But of the many rooms in this house, some may only need some aesthetic upgrades, while others may need an entirely new design, and still others may need to be demolished entirely. Thinking ahead to 2060, one of the first steps in pushing forward may not be to consider innovation purely for its own sake, but alongside the parts of the “old” that we want to disrupt.

When asked what he would do with the 5 million dollars, Harris said that he would create an ongoing task force to do personal work around identity and morals, examining the effect of biases on funding, casting, personal interactions, and plays themselves. Through this lens, the fundamental question of the theater of the future would not be about spreading the gospel of theater as it currently stands. Rather, it would be about questioning the assumptions that underpin the ways that theater is created, performed, and marketed, since these assumptions might be creating the very problems we are trying to solve.