Leaping across time

Lately, a friend and I have been talking about Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Over and over, the book makes me question the gaps in academic history curricula and pop culture. Why didn’t I learn about the Dominican Republic’s fraught relationship with the U.S. until I was a senior in college? Why did I feel like I’d never met (nerdy, hilarious) Oscar de León on a page before, while I’ve always found it impossible to escape the Caulfields and Gatsbys of the book world?

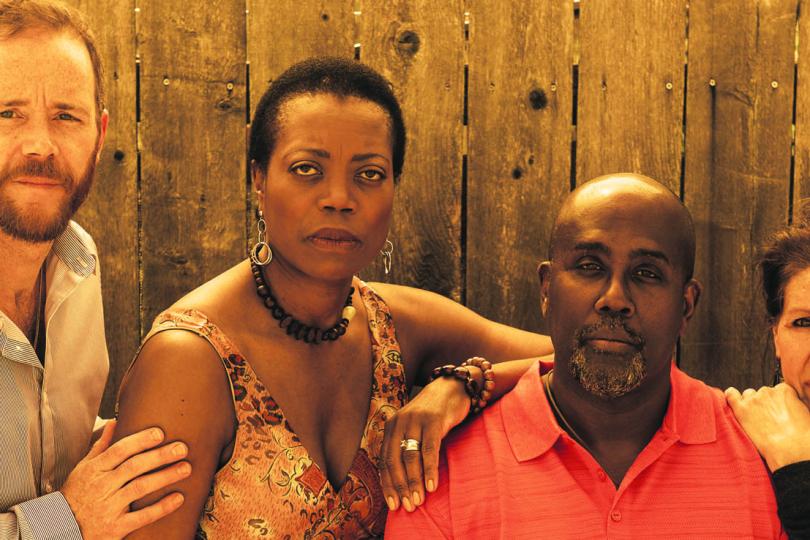

Provoking similar questions, Pillsbury House Theatre’s Scapegoat is a two-act drama about people affected by the Elaine, Arkansas race riot of 1919, in which white men murdered hundreds of black sharecroppers (effectively for trying to unionize). The first act leads up to the riot, opening just after white sharecropper Uly Gibson (Dan Hopman) murders black couple Effie and Virgil Hillman’s (Regina Marie Williams and James A. Williams) only son. Even though their son had done nothing wrong—he’d actually given Uly’s abused and penniless wife, Ora (Jennifer Blagen), food—he is a titular scapegoat, taking all the bile of Uly’s prejudice and hate.

The second act fast-forwards to the present day, with the same four actors playing married couples—but this time, the pairs are interracial. They’re travelling together and pass through Elaine, Arkansas, eventually finding out about the area’s history while discovering even more about each other.

Dealing with the past

According to the Scapegoat program, writer Christina Ham conceptualized the play after “a discovery of Ida B. Wells’ book The Arkansas Race Riot.” Like many others, Ham had never heard of the 1919 events before—even though they’re the deadliest racial conflict in the country’s entire history, and they led to a landmark Supreme Court case—so she started researching the topic. “Arkansas hasn’t dealt with it. They’re embarrassed about it,” she told the Pioneer Press.

In addition to informing audiences about the race riot, Scapegoat looks into the fallacies of the capitalist, “post-racial” world. Jennifer Blagen’s Ora Gibson is basically the voice of Marxism in the first act; she wonders why she’s not supposed to associate with black people (questioning social structure), and she imagines that life would be easier if the two races would work together (visualizing a proletariat). “Seem like we all just fightin’ over pennies,” she says (poking at capitalism’s useless endgame). “Ain’t the same chains [that restrain Effie and Virgil] bind us too?”

Like Ora’s questions, the staging worked on several levels. Ora spends some time in an aisle, so when Virgil shoos her off their property, he points his gun at the audience. Effie spends lots of time at center stage, which is the right spot for a woman of color to be. The couples’ spaces, parallel house/hotel room interiors designed by Dean Holzman, are spookily separate until the second-act characters cross their invisible lines.

Ham’s dialogue is stately and smart, especially in the powerful first act. The 1919 characters lean heavily on farming figures of speech; they’re all sharecroppers, so the soil is their frame of reference. “Fruit,” “cotton,” “field,” “crops,” and “harvest” come up as metaphors.

Small flaws creeping in

The already-long first act, though, could benefit from having its last scene cut. Just before it, Effie and Virgil rally a group of black sharecroppers at a church. Then, Uly kick-starts his own rising action by saying he’ll stop the union members. Based on prior foreshadowing, however, the audience already understands how that will lead into the massacre. His last words aren’t really necessary.

During the second act, all four characters had some sharp points about each other’s flaws, but they stayed impossibly blind to their own. “You take the C train because you choose to,” Elaine (Blagen again) says to illustrate Russ’s (Hopman) privilege, but she’s the one who’s just taken egregious selfies at a plantation. Soon after Greg (James A. Williams) ridicules Russ for not talking to his biracial children about race, saying that he’s educated his own children about their collective past, he says, “Like most Americans, I’m comfortable being ignorant about history.”

Later, Russ teaches a clueless Elaine about the history of miscegenation laws, but he’s the one who won’t bring up race with his kids—who, by the way, are named Egypt and Kenya. Of course, people are full of contradictions in real life, but these went too far to be believable. It felt like the writer stopped letting the characters speak and started lecturing them herself.

Minor criticisms aside, Scapegoat is a powerful play. Regina Marie Williams stood out for her intense, well-rounded portrayals of both Effie and Paula Barnes. The whole cast, in fact, seemed unrecognizable for several seconds after Act II began, which is a testament to both their skills and Trevor Bowen’s work as costume designer. The story works on both the characters’ personal level and the broader historical level. Directed by Marion McClinton, Scapegoat grips audiences and raises important questions.