REVIEW: 'Detroit' at The Jungle Theater

Review

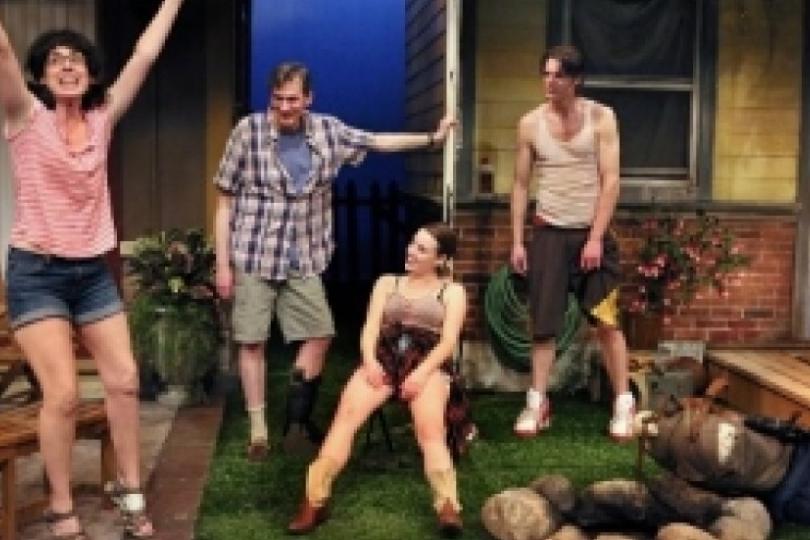

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: You should go and see Detroit. The performances are sexy and intense, the direction and design (by Joel Sass) are remarkable without calling attention to themselves, and the script is filled with great lines and the occasional shocking event (I feel the need to call attention to Wu Chen Khoo’s technical work at this point, for reasons that would spoil the surprise if I explained them). The Jungle has developed a reputation for great design that doesn’t scream “We spent a lot a lot of money of this,” (though they probably do) and for working with a consistently impressive stable of performers. I have differing opinions depending on the production (of course) but I’ve rarely been disappointed by a Jungle show.

And yet. Watching Detroit I was continually reminded of a review in The New York Times I’d read earlier that week for Will Eno’s Broadway debut, The Realistic Joneses. For those of you not familiar with the name, Mr. Eno has been a bright star in the new play world since 2005’s Thom Pain Based On Nothing, with critics tossing around phrases like “the post-modern Beckett.” And, indeed, Mr. Eno plays with form and language quite a bit, though, strangely, a description of The Realistic Joneses would not be unfamiliar to anyone who’s sat through Detroit.

No, I’m not accusing either playwright of plagiarism. When I came to Minneapolis as a Jerome Fellow in 2003, Lisa D’Amour (the writer of Detroit) had just been awarded a McKnight Fellowship—this made her roughly the equivalent of a Senior to my Sophomore, in high school terms. She was so cool. Because the culture of The Playwrights’ Center is so vibrant, I saw readings of many of Lisa’s plays —performances as well. All of them adventurous, exciting and unique – two of them (Anna Bella Eema and Cataract) close to masterpieces. But sitting through Detroit, remembering that review of Realistic Joneses, I started to wonder if there’s an unspoken rule for adventurous playwrights hoping to transition into the mainstream. Yes, we’ll let you in, sure – but only if you give us some version of Virginia Woolf ‘cause that’s as adventurous as we’re gonna go. You could even stretch Tracy Letts’s journey from Bug to Killer Joe to August: Osage County in a similar way (what is August, after all, but Virginia Woolf with an extended family?). Sarah Ruhl managed to escape this trajectory, but only just - Vibrator Play also marks a turn toward less formally expansive work. As does Thomas Bradshaw’s Intimacy. And Gregory Moss’s recent Reunion at South Coast Rep in California.

Am I saying these writers “sold out” or were somehow consciously pressured to? Of course not. Being a professional playwright myself doesn’t just make these reviews ridiculous - it also gives me insight into the day-to-day realities of the business. It’s merely an observation leading to a question: Are producers and artistic directors so nervous about mainstreaming formally adventurous writers they only perk up when that writer has finally written something not-so-damn adventurous?

This brings to mind The Jungle’s beautiful production of Waiting for Godot in 2012, a play considered extremely adventurous when it premiered 59 years prior to Bain Boehlke’s loving interpretation – that still had audiences walking out at intermission (I seen it with my own eyes). So perhaps producers and artistic directors are correct when they encourage writers to apprentice themselves to Beckett, but move on to Albee when they’re ready for the Big Leagues.

When I was lucky enough to get a residency at The Edward Albee Foundation in Montauk, I asked Mr. Albee what inspired him to create the foundation in the first place. “Tax dodge,” was his brusque reply. Was it joke? Was he being mean for the sake of being mean? Was he actually being mean? Was it all three? I’m still not sure. But this quality of Mr. Albee’s gives the characters of Virginia Woolf a flesh-and-blood sense that’s sometimes lacking in the play’s many children and grandchildren. To be fair, Ms. D’Amour calls Detroit a fable, and many of the characters do reach toward a modern version of Commedia (John Middleton, for example, does beautiful work with The Nerdy White Guy So Ashamed Of His Nerdiness He Lets An Obvious Psychopath Become His Best Buddy). We know these characters (from the world of theatre) and so we like them.

And we have fun watching them. I also suspect (hope) there may be more than a little irony in the “lessons” learned by the end the piece (though if so, it was lost on some of the people I saw it with). No, all of Ms. D’Amour’s considerable theatrical talents are packed into Detroit - that’s why it’s worth seeing. But having experienced so much of her other work – especially Cataract and Anna Bella Eema - I can’t escape the thought that somehow her heart just isn’t in it.