The State of Sound Design in the Twin Cities

A successful sound design can create a deeper connection between the play and its audience: defining environment and emotion, clarifying voice and intent. With subtlety and psychology, sound design is the creative and technical process resulting in a complete aural environment. Theatre needs sound design to focus the ears of the watcher just as acutely as lighting design focuses their eyes.

Over the last twenty years, the sound designer has become a critical collaborator in American theater. It would be difficult to find a theater company these days that doesn’t recognize the need for modern sound design. However, the relative youthfulness of the field and its intangibility often lend themselves to the entire artistry being overlooked and misunderstood by producers, critics, and audiences.

In the most public and recent example, the Tony Awards’ decision last year to eliminate sound design as an award category has added to the frustration sound designers feel. After six years of distributing awards for Sound Design (Play and Musical), the Administration Committee decided that it is no longer appropriate for the Tonys to acknowledge those artists on a regular basis. Some anonymous members of the Committee reported that the decision was driven largely by three factors: Lack of relevant expertise, a disinterest in edification, and a belief that sound design is more technical than artistic. The outrage from the national sound designer community—and their allies in other theatrical disciplines—has been vocal and aggressive.

If this ignorance has invaded even the top echelon of New York theater, what does it say for regional theater scenes, including our own? What is the state of sound design in the Twin Cities?

RESOURCES

In the pursuit of creating a sonic experience for audiences, Twin Cities’ sound designers can often find themselves stymied by a series of hurdles: paltry budgets, sub-par equipment, a dearth of skilled labor, and a generally unsteady system of artistic support.

“If there is a weak spot in the sonic capabilities of our community it’s the fact that sound systems and sound budgets at some of our smaller theaters and universities have been completely neglected since the twentieth century,” said composer and sound designer Michael Croswell, who notes that he often finds himself donating the use of his audio equipment. “[They] simply do not have the resources, expertise, or administrative/political will to keep up with what is happening with emerging audio technology.”

A recent Pioneer Press article discussed a growing trend in Twin Cities theaters of all sizes to produce musicals, however there was no mention in the article of whether the producing venues are equipped to support the acoustics that performers need and audiences expect. The condition of a theater venue’s audio equipment speaks volumes of the value that theater places in sound design.

“I don’t think there is always an appreciation of how important technological upgrades, and consistent funding for them, could improve the state of sound and give designers a chance to expand upon and improve their final product,” said designer and University of Minnesota theater instructor Montana Johnson.

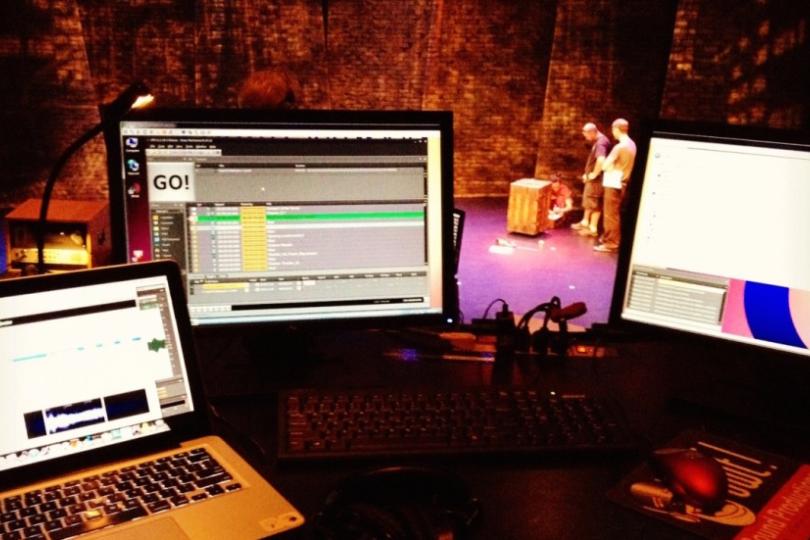

An informal survey of theaters with permanent homes in the Twin Cities examined the state of sound equipment and budgets around the metropolitan area. Twelve of fifteen theaters replied and, of those twelve, eight theaters have knowledgeable, if not dedicated, audio staff on hand. However, only five have made major audio improvements or upgrades within the last five years. (Five-and-a-half if you count Park Square Theatre’s new sound system for their new stage). Overall, only two of the respondents have a yearly budget for sound, while only two others regularly set aside money for maintenance. All theaters, thankfully, run current versions of show control software, QLab or SFX.

When equipment, staff, and money is scarce or unreliable, as this survey indicates, designers are forced to balance artistic demand with technical capability. This means that the time it takes to fix problems, and acquire and set up gear (often times with no added compensation), takes away from time spent improving the design.

BUDGET PRIORITIES

For some theaters there is often an ignorance of the upgrades and maintenance a sound system needs. For others, it’s a straightforward budget issue.

Penumbra co-artistic director Sarah Bellamy explains that her theater attempts to focus first and foremost on the designer before the equipment (which is regularly maintained by production manager Allen Weeks). However, “I don’t think we’re where we’d like to be,” Bellamy admits. “[Equipment] is not where we’ve invested most heavily. And that’s part of the issue of having a budget that’s to the absolute limit and even beyond. We’re trying to do so much with so little.”

In fact most theater technical directors and production managers admit that budgets for audio upgrades are often inconsistent, many times sourced from grants acquired every few years.

“We do budget for technology upgrades and repairs in our annual budget, though it's a small theater with a small system and a small budget,” said Ryan Ripley, Associate General Manager at the Playwrights’ Center, which upgraded its sound equipment thanks to a grant from the McKnight Foundation. “Since most of our PlayLabs and Ruth Easton writers choose sound design as their production element, this budget has been a little more skewed toward sound in the last four years.”

Park Square Theatre Technical Director Rob Jensen explained that equipment is expensive and difficult to justify when faced with income projections in an overall budget.

“It’s the big ticket items that are easy to remove when it’s crunch time during the budget process,” he said.

Yet Jensen is cognizant of the need for improvements to Park Square’s sound system, including the possibility of creating a position for an in-house sound supervisor to oversee implementation of audio equipment (thereby freeing the designer to concentrate on the design).

Veteran sound designer C Andrew Mayer simplifies the situation. “All it takes is a small investment and the quality goes up,” he said. “For instance, having subwoofers is the difference to me between a professional situation and [an amateur] situation. Theatres need to have gear and they need to commit to having people around who know how to work the gear.”

DECIBELS TO DOLLARS: MAKING A LIVING

If the budget money isn’t being spent on equipment, are sound designers rewarded for the extra work they do? Can an artist afford to design sound full-time, as a primary source of income?

“There are plenty of opportunities to work, but as a full time gig it’s very tricky,” said Johnson. “Locally only [a few theaters] pay design fees of the kind of numbers that make doing less than 20-plus shows a year possible.”

And while sound designer and teaching artist Peter Morrow, a recent transplant to the Twin Cities from Dublin, Ireland, has been impressed with the amount and quality of work the area offers, he says, “I don't think working exclusively as a sound designer for theater is a realistic thing in the Twin Cities,” he said. “It does seem like, apart from a few jobs in larger institutions, it’s pretty hard to do just sound design and pay the bills. Without [teaching] I'd be struggling much more financially.”

A survey of local sound designers found there are few who are able to make a living solely off design alone. Of the survey responses, over 80% consider themselves freelancers, with half of those balancing the demands of at least a part-time job in addition to designing. Sixty percent of those that identify as freelancers have been designing in the Twin Cities for five or more years, but only half have received a stipend increase (from any theater, of any monetary size) within the last year.

ADVOCACY

Despite the growing presence and recognition of sound designers in the American theater, we continue to lack a consistent vocabulary for evaluating and discussing sound design outside the field. There seems to be a perplexity about how to get audiences, critics, and producers to notice, evaluate, and appreciate sound.

“There is a huge lack of education about the complexity and artistry of the work,” said Bellamy. “I don’t know that theaters - institutions - do a good job of helping audiences value all the elements that go into a play. And that’s a space where producers and theater companies could be better advocates.”

So could designers themselves. Though a successful sound design usually maintains a low profile, that shouldn’t necessarily mean the same for the designer.

“Within the community itself, we as a group don’t do a lot of saying what we need. I would argue that it would enrich us all if the relevant people were better educated,” said lighting designer and theater educator Wu Chen Khoo, who recently created Technical Tools of the Trade - an education and outreach program that aims to bring the public and artists together through the technical and design aspects of the performing arts.

There is no official body representing sound designers in the Twin Cities, however many theater designers of all disciplines believe there needs to be a closer-knit, more unified local community with a louder collective voice. Were a guild or association to be created, designers (sound and otherwise) may find strength in the necessary numbers to effect change in equipment upgrades, budget, education, and stipends.

CONCLUSION

It’s difficult to create an immersive theatrical experience when you don’t feel artistically supported.

By giving sound designers the tools to truly participate in a production, on par with other design elements, the total theatrical performance and all of its elements is elevated. In order to create the best production for our audiences, theaters need to examine their budget planning in every season and examine if they are doing what they can to support their sound designers. Critics, producers, bloggers, and Ivey Award evaluators should educate themselves on what makes a good sound design, and recognize the impact a design has on a story and its audience.

Designers themselves could also stand to speak up and do that educating. The artistry and careful craft that we constantly create is undeniable, but we do ourselves a disservice when we steadfastly remain quiet about our work and its importance. By shunning the spotlight, we risk devaluing our craft.

When we brush off the collaborators who make theater happen, we betray the principles the very audiences for whom we create value in us. Sound design is a valid part of the performing arts landscape and it should be valued. The Twin Cities theater community respects its designers better than what’s currently occurring on Broadway, but we’re never far away from falling into the same trap.