Tracking identities

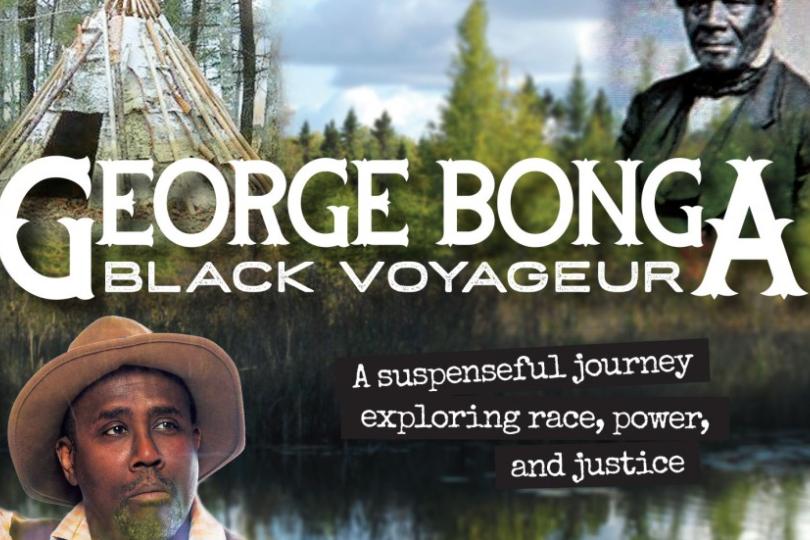

On paper, George Bonga: Black Voyageur looks like just about as straightforward a title as you could ask for, a simple spelling-out of the protagonist’s name, race and occupation. Midway through the first act, though, it starts to become clear that that title is hiding a fair bit of irony, and maybe even a bitter joke. Like just about everything in George Bonga, there’s more to the name than meets the eye.

Based on a real-life tracker and fur trader who became a living legend in Northern Minnesota in the mid-19th Century, James A. Williams’s Bonga contains multitudes - multitudes of multitudes, depending on who you ask. In George’s own eyes, he’s a well-educated, self-made, independent man who just happens to be the son of a black father and an Ojibwe mother, born into a community where people of color are so unheard of that any non-Native is classified as “white” by default. To the white townspeople who rely on his skills, he’s a friend and colleague, but also a curiosity and a useful bridge between white and Native cultures. To his Ojibwe wife he’s a proud but somewhat foolish man who doesn’t want to acknowledge that his own ambiguity about his background isn’t necessarily shared by those around him.

For the purposes of George Bonga: Black Voyageur, though, possibly the most important perspective is that of Che-ga-wa-skung, a young Ojibwe murderer whom Bonga is tasked with tracking. Bonga’s pursuit and capture of Che-ga-wa-skung helped cement his place in history and eventually led to what is generally agreed to be the first murder trial in the Minnesota territory, but Carlyle Brown’s script is more interested in the dynamic between a damaged man who defines his life by the indignities visited upon his race and a prosperous man who has managed to thrive both because of and in spite of his.

A complex pair

The interplay between Williams’s Bonga and Jake Wald’s Che-ga-wa-skung is the meat of the play, and it’s a pleasure to watch. WIlliams plays Bonga with a fierce pride and dignity that never quite spill over into pomposity. He seems to like his captive well enough, and isn’t above sharing a joke and a smoke with him, but he’s not about to be coerced into shirking his duty. Che-ga-wa-skung seems likewise fond of Bonga even as he needles him constantly with questions about race and identity and fairness. Wald portrays him as a desperate hustler trying to talk his way out of trouble, but also as a bright and genuinely inquisitive spirit trying to get to the bottom of some impossible questions.

As the relationship between the two men wears on, Williams allows subtle notes of wary self-doubt to break through Bonga’s barriers, while Wald’s delivery grows more pugnacious even as he teeters on the brink of existential crisis. The questions of identity come fast and hard, vacillating between activism and devil’s advocacy: Why does Che-ga-wa-skung’s punishment depend on whether his mixed-race murder victim is deemed white or Ojibwe? Can the free-born Bonga truly empathize with black slaves south of the Mason-Dixon line? If Bonga is legally a white man, why does he still cringe to remember the boarding school classmates who loved to run their white hands over his “beaver pelt” hair?

If there’s a knock to be made against Carlyle Brown’s dialogue, it’s that these overt questions sometimes threaten to overwhelm the narrative. Still, while there are a few passages that feel a bit like listening to a history lesson or a humanities debate, Williams is such a confident, commanding stage presence that it’s tough not to become immersed in his performance. Wald proves a worthy foil, investing Che-ga-wa-skung with bitter wit and the wistful sadness of a man who can see the bigger, uglier picture.

Fluid and inflexible at once

A play filled with this much conversation and this many big ideas always runs the risk of drowning in its own ideology, but director Marion McClinton keeps the narrative propulsive. The sequence in which Bonga tracks Che-ga-wa-skung through the frigid northwoods is particularly tense and suspenseful, with the fugitive scrambling to predict his pursuer’s next move and the tracker coolly moving toward what he sees as his inevitable victory.

There are subtler symbolic touches laced throughout the show as well. Native characters populate the stage in virtually every scene, often as part of the primary action but also rocking quietly or moving boxes in the background. Regardless of what Bonga or his fellow infant Minnesotans might think about their own mixed heritages, it’s clear that pushing race to the margins still can’t remove it from the frame.

George Bonga may have been a black voyageur as far as the high school history books are concerned, but Brown and McClinton present a complicated portrait of a man caught between cultures in a time and a place where identity was both fluid and inflexible.