Frank Theatre’s production of

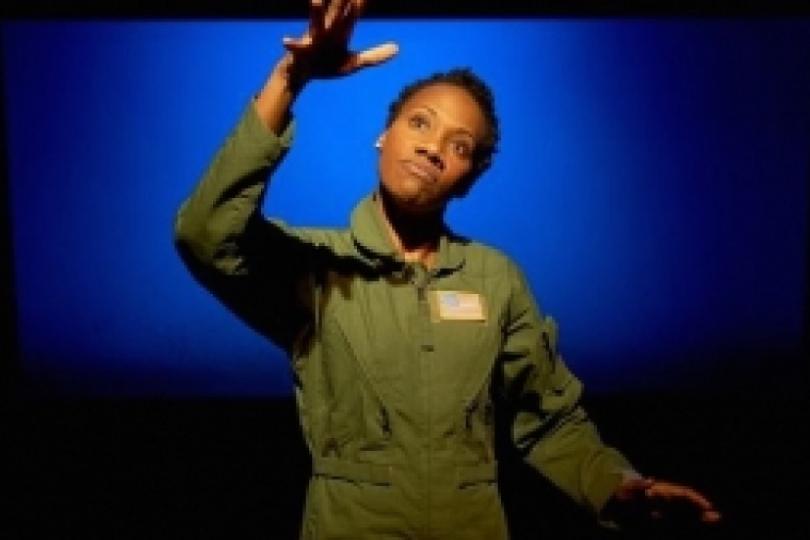

Grounded, a newer play by George Brant, crackles with the kinetic energy of its sole performer, the tremendous Sha Cage.

From beginning to end of this one-woman show about a fighter pilot, Cage maintains such powerful physical presence, verbal precision, and vocal control that the audience has no other option but to be consumed by the character she creates. And it is her character. She owns it, fully inhabits the woman she plays, a skill of critical importance in solo shows. Few actors could summon such a rich and layered person, or a performance of this quality, from a pretty flawed play.

And it is a flawed play. Cage carries it off; go see her in this, as in anything else she does. But the script she has to work with feels troublingly unfinished. It needs something—another draft; a dramaturg; or someone who could correct the misperceptions written into the play.

The story centers on a female fighter pilot who’s giddy in love with her plane, her uniform, and above all, “the blue,” as she refers to the sky. The Pilot is young, smart, successful, and proud, and she’s found a place for herself at the bar and in the ranks of the military men she calls, “Her Boys.” She’s brash, ballsy, and has the bearing of a loose-limbed young man. Cage is strongest in this iteration of the character—the young pilot—and that strength will continue to burst through the script throughout the play, each time electrifying the room.

And that’s the trouble—the play keeps trying to push this thrilling woman into a pre-made plot that doesn’t fit. The play spans only a few years, which should keep it tighter than it does. Instead, it seems to take place in three nearly separate lives.

From the Book of Plots: The One with the Baby

We are just barely getting to know the young pilot when she gets pregnant. This in itself seems like an unexpected development, even though the show’s program says it will happen. It seems to divert the play from a story about this character, this

particular character, or the military, or war, or all of the above. Suddenly you’re watching a play with an obvious setup (career gal gets knocked up), and a predictable storyline (career gal worries, makes difficult decision, has baby/doesn’t have baby) and a totally flat outcome (gal, now depressed and un-maternally ambivalent, deals with shitty consequences either way). Immediately, you’re yanked out of a work that explores pressing political, personal, and social questions—Frank Theatre’s usual métier—and stuck into the realm of the tried and true. We’ve asked this question for fifty years—Can Women Have It All?—and we get the same old crummy answer: Sort of, sort of not. An unresolvable narrative about the perplexities of masculinity v. femininity, family v. career, would need to come at the question from a radically new, fresh perspective if it was going to shed new light. Making the character a fighter pilot does not do the trick.

Soon grounded and on leave, the script moves the pilot so quickly from her happy pregnancy to her sudden marriage to her abrupt condition of young wife-ness that it presses at the edges of believability. Cage does a hell of a job carrying over as much of the personality of the young pilot as she can, but now the script as it is written becomes a tangle of incongruous motivations, actions, and words.

Returning to her base a few years later, she finds that her beloved plane is gone. (“Is this how you punish me…for getting pregnant?” she asks her superior officer, which, come on.) In short order, she’s transferred to Nevada with husband and child and trained to operate 11 million dollar drones.

Here’s where the play should have shifted back into high gear, both energetically and in terms of plot. Focusing on the fascinating, seriously important issue of contemporary war games, we follow the pilot willingly into a new war.

The early stages of this segment of the play are surreal and strong, and the audience is drawn in by the pilot’s growing fascination with the war she’s watching, her hand on the joystick, eyes trained on a screen a few inches from her face. There’s the distinct sense of being trapped in a video game, detached from a physical reality of any kind, and this is effectively conveyed by a gradual shift in Cage’s relationships in the real world. Her marriage deteriorates. Her relationship with her daughter becomes half-hearted. Her point of view gradually merges with the eye of the drone, scanning miles and miles of a landscape that begins to haunt her dreams.

The playwright has tapped a rich vein here, where he could explore truly hard questions about how war is fought, what is right, what is wrong, and whether modern war can truly end. Cage’s narration of this section forces our own eye to match hers, and, our attention focused on her rapid-fire description of what she sees, we are led to the final section.

From the Book of Endings: The Crazy Person Conclusion

Then there’s a significant amount of unraveling, some of it intentional, most of it not. At this point Cage is dealing with a script that’s departing markedly from its own logic, and she does this admirably, infusing the last section with the same energy she has carried through all along. But now—and this really annoys me—the playwright has her go mad.

This is the Crazy Person Ending, which in war narratives, especially recent ones, tends to manifest as a sketch of PTSD. The Crazy Person Ending in this case is an unfair choice, one I really believe the playwright should not have made.

From the point at which the pilot’s mind begins to shift, the remainder of the play is blurred and indistinct—not in such a way that it shows us the character’s own growing confusion, but in a way that suggests confusion on the playwright’s part. This section should show us the face of a person driven out of her mind by the dissonance within herself and her life. Instead, there is a clear lack of knowledge about what PTSD actually looks like, and some pretty problematic Generalized Crazy Person behavior.

Military precision gives way to a heavy-handed metaphor. Where a moment ago we were watching the pilot maneuver an enormous machine in the sky with the slightest turn of her wrist, we are now mired in an examination of the amorphous boundaries between self and other, right and wrong, seeing and being seen.

Paradoxically, this variety of ending—the Crazy Person Conclusion—is too convenient. In a play about difficult decisions, wherein the plot hinges on a choice the main character needs to make, you can always leap into the metaphor of madness.

The play can’t have it both ways—the story of hard choices vs. the resolution of no resolution at all. The character never actually has to make the hard decision. Neither does the playwright.

With this remarkable performance by Cage, it’s particularly troubling that the character is never allowed final say. The pilot Cage gives us is fully prepared to end this play on her terms. Instead, the last section of the play drains her of vibrancy and strength. Certainty, it could be saying something about the way war can break someone down. But that is not what it says. It says she was caught in an interior war, and she lost. And that is something Cage’s pilot would never have allowed.