Where the words are

Joseph Stanley paints his set with words for The Language Archive—letters and characters from Mandarin, Hebrew, Greek, French, Arabic, and Korean. These careful strokes cover cupboards, walls, and bookcases with sweeping grace--reminding us of the beauty in the language.

And Julia Cho’s script is a celebration of the nuances of language, of the necessity and distraction of words, as well as of the humor and pain relationships hold. At the heart of her script stands a failing marriage: Weighted with sadness, Mary (Sara Ochs) leaves her linguist husband George (Kurt Kwan) in the first scene. Why? She realizes that they no longer speak the same language. The disconnect was breaking her heart.

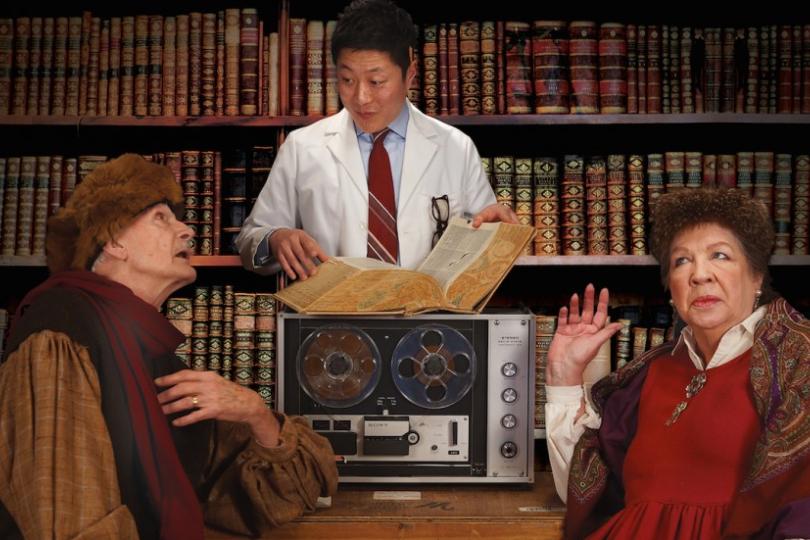

Meanwhile, George and his assistant Emma (Emily Grodzik) try to work with and record Alta (Claudia Wilkens) and Resten (Richard Ooms), long-time couple and last-living speakers of the Ellowan tongue. Alta and Resten, however, have sworn to ignore one another until the other apologizes. Throw in a dash of magical realism, lots of well-timed humor, and strong ensemble work—and you have Rick Shiomi’s production of The Language Archive churning these plot lines together into a humorous exploration of (mis)communication.

The language of emotion

Kwan’s infuses George with angst so honest you cannot help but laugh: shaking his head in confusion, he informs the audience, “[My wife] cries all the time. She cries when she makes salad.” Sure enough, Sara Ochs’ Mary tears up while dusting the house, while turning away from her husband, while confronting all the emotions resonating through her body. In their first argument, George tells his wife, “It’s not normal to be this way;”crying all the time seems so odd. Mary insists that, in response to deaths in the family, surely “the normal reaction--the human reaction--is to mourn.”

Then, when Mary turns to her husband to tell him she is leaving, we see the heartbreak in both Ochs and Kwan, their eyes shining with longing for something lost. George turns to the audience to offer a desperate monologue in reply--a barrage of “Take it back!”--but to his wife, he awkwardly offers: “Don’t...go?” Her hopeful face falls as she realizes her husband cannot even find the words to fight for her to stay.

Later Mary explains the depth of her emotions: “There are so many reasons for weeping--how beautiful something is, how true [something is], how I am going to die,” and Ochs embodies quiet depletion. She blames no specific incident or particular fault of her husband--rather, she just realizes that she no longer has a reason to remain with him and stay so sad.

Wilkens and Ooms as Alta and Resten counteract such sadness with their skillfully-staged bickering. An older couple from far away Ellowan, the two only to speak English since “only angry people use English.” They delve into an entire long marriage’s worth of arguments with brash childishness, infectious energy, and utter hilarity--but, again, only in English. Their mother tongue, Ellowan, the two agree, “sounds like song” and reminds them of the movement of rivers—utterly unworthy of such fighting words.

What words are enough?

Throughout, Cho’s writing raises fascinating questions. From Mary: Why do we cry? What is considered normal? What is the line between needing to leave and needing to stay?

Through George, the audience hears his belief in the foundational importance of language. He shouts at the Ellowan couple, overwhelmed by the parallel to his own inability to speak to his wife: “A whole world is slipping through your fingers--and you won’t even fight for it!” Yet Alta shakes her head and replies with sadness, “You think loss of our language is loss of our world...but worlds die first, then language follows...No amount of talk talk talk will ever bring what is gone back.”

So what does die first: Worlds or languages? When do our words fail? And can you ever really get something (or someone) back?

George walks into a bakery months later to find Mary baking bread, her face shining with joy at her newfound livelihood. He has summoned the words to ask her to come back. He finally understands that the language of a marriage transcends the actual words used but rather captures the subtext and history and emotions embedded in each question. But he is too late. And his perfect sadness complements her perfect peace.

These two love stories—of Mary and George, of Alta and Resten—intertwine with another unorthodox story, assistant Emma’s unrequited love for her boss, George, while Robert Gardner and Melanie Wehrmacher’s work in the ensemble pokes and prods the other characters along their paths to untangling the nuances of language.

This smart script finds beauty in tears, freedom in leaving, and silence in conversation; yet it also celebrates the loyal bonds we preserve, the healing that follows them breaking, and the hope for “a symphony of notes that no longer exist.” It’s an intriguing piece that provides just as many laughs as tears and linger with you far outside the theater.

Do we really mean the words we say? Which words do we offer to whom? And are words ever enough? In Ellowan, “I love you” translates to “I never want you to leave me.” Maybe that is the best example of saying what we truly mean.