Art for social change: what change are you looking for?

With the explosion of political art following the 2016 election, maybe it’s time to gather and look at what makes this kind of art effective. Are enough artists confronting what they want their work’s outcome to be? In delivering political messages, is it best for them to layer them subtly into a play or to flat out tell people what they should be doing?

In short: how can we best make art that inspires the actions we want?

These questions were the core of the conversation at the first of five Artist as Citizen talks at Phoenix Theater. Meeting once a month to discuss artists’ roles in politics, hosting group American Civic Forum aims to get people out and talking to each other about how to make political art more effective.

Below are some steps the talks unearthed, including a need for artists to be more clear about their goals, to meet their audiences where they are at and to acknowledge the work of activists who have already been doing this.

Be explicit

Starting the talk, Forum president Matthew Foster presented graduate research and observations from 15 years working at the Minnesota Fringe Festival and elsewhere in the art world. Plays have a great capacity to deliver political messages, he said, but some artists could do more to translate them into concrete steps.

“One of the first things that artists have to think about if they want to make political art is choosing what they want the art to do, and that’s what I see most artists are reluctant to do,” Foster said. “They are reluctant to sit down and say, ‘I want to have this particular outcome from my work.’ Some do, but artists are really trained to shy away from being that explicit about what they want the outcome of their work to be.”

Attendees suggested, why not use these pieces to tell people about which representative they can call? Or they could direct audiences to an organization (better yet, one awaiting them in the lobby!) they can approach to talk more about the problem? This would also work to connect different groups, like artists and activists.

Know your audience

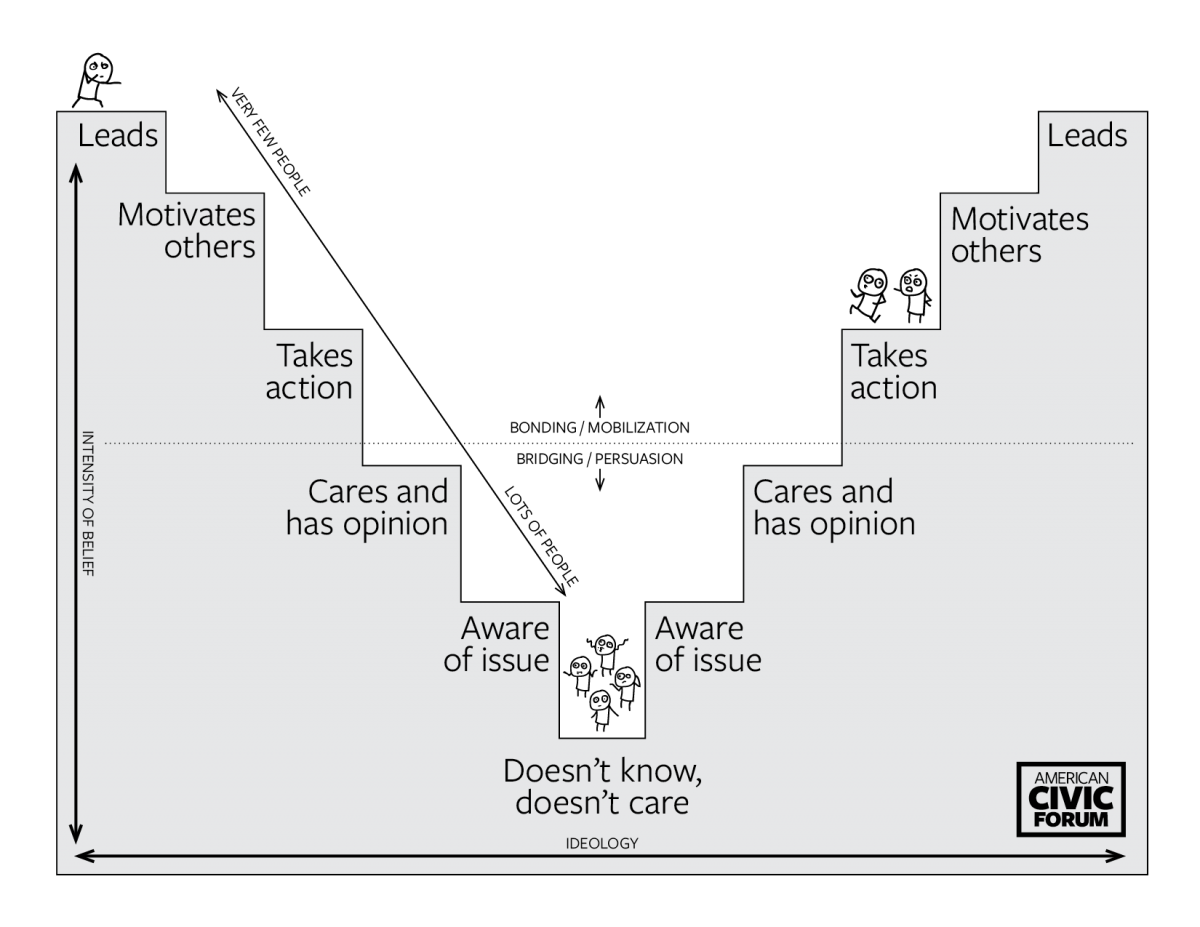

Foster said political art can serve one of two purposes, but not both at once: it can either create connections between different groups (“social bridging” or persuading), or it can make ties within a group stronger (“social bonding” or mobilizing).

It all comes down to knowing your audience. In the Twin Cities, audiences likely fall into the second group that is already informed about an issue, and votes. Knowing that about them, why spend half of a show trying to explain an issue they’re well aware of? Why not use that time to urge them to do something about it?

On the other hand, if an audience is divided or at different levels of awareness on a topic, that’s a great opportunity to expose the issue, and with that audience, creating that connection is enough for one show.

There’s a spectrum, Foster said (his illustration above): at one end, there are people who don’t know or care about the issues. At the other, there are leaders who mobilize others to change things. He contended that you can’t get people to leap from one end to the other. Rather, you can get them to take a step toward being more informed and likely to take action.

Respect activism’s history

With such charged political changes in our country, groups of people who might not have felt a need to make political art before are entering an arena that others have occupied for far longer. On the surface, the small group that attended this discussion was mostly, if not all, white. But less clear was whether these people were artists or activists; new or used to political art. For those coming into the practice of art as activism for the first time, Foster said via email after the discussion, a little understanding of the past goes a long way.

“Artists and art have been the center of community-building and political change in many communities for decades and decades — and not just in communities of color,” he said. “It's critical to respect that history and those spaces, particularly if you're trying to use your art to bridge constituencies. It's important to understand that, if you're trying to bond an audience together, there have to be pretty strong ties that already exist.”

Your work alone will not solve everything; it’s one of many efforts to bring art into activism — all the more reason to give it a precise message and action point that fits its audience.

“I can't just wander into any theater and announce that I'm there to save the whole of the American republic with my shows or this model,” he said. “And anyone who thinks that they can do that should take a few really, really big steps back.”

Let’s end this recap about concrete steps with a concrete step: if this sounds important to you, take a look at when the next talks are (listed below). If you know a way to bring more diverse voices into them, share.

All meetings are at Phoenix Theater, 2605 Hennepin Ave., Minneapolis. Read on the organization’s website.

The Unbearable Lightness of Political Comedy

Monday, March 27 at 7 p.m.

From late-night TV to stand-up, comedy has earned an enormous place for itself in U.S. political culture. But when court jesters speak the truth to the crown, does the king get the point? Does the audience?

Choir, Meet Preacher

Monday, April 24 at 7 p.m.

As artists, we’re often told “don’t preach to the choir”—but doesn’t the choir need to hear a good sermon sometimes? Why do we shy away from making art with rousing, explicit political messages? And why do we consider audience interpretation more valid than artists’ intent?

Our Subversive Heritage

Monday, May 22 at 7 p.m.

Throughout history, artists of all disciplines have made works and provided labor to propel social and political movements forward. How do we draw inspiration from the plays, songs, paintings and other works of our past—and harness the energy of this proud tradition?

The Facts of Art

Monday, June 26 at 7 p.m.

If many Americans get information about politics, law, science and history from popular culture and the arts (and they do), what is the responsibility artists have—if any—to stick to facts when they’re creating art?